Planned Industrial Settlements Zone

Summary of Dominant Character

Figure 1: Pit winding wheels are often set up as memorials to both killed workers and former collieries in these communities. This example, from Cortonwood Colliery, is adjacent to Brampton’s war memorial.

© 2006 Richard Whitman, reused according to creative commons licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

The dominant characteristics of this zone are regular and large scale patterns of two storey housing, mostly built to garden suburb plans and, as such, including generous provision of open and recreational space and institutional buildings within an ordered and coherent overall plan. These settlements were developed in the early years of the 20th century, to house coal miners and their families.

The overall style of these communities is generally marked by geometrically planned estates of brick built and pebble-dashed cottages (sometimes semi-detached houses, but more usually short terraces of 4 or 6 houses). Strong ‘garden suburb’ influences are clear, although at Wath the earliest phases have more in common with the ‘Grid Iron Terraced’ zone, due to their higher densities, less coherent overall plans and longer ranges of conjoined housing.

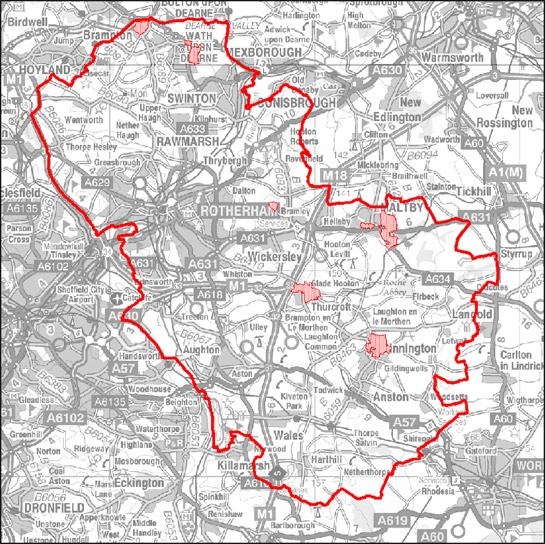

Figure 2: Location of character areas making up the ‘Planned Industrial Settlements’ zone within Rotherham.

Base mapping © Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Sheffield City Council 100018816. 2007

The significance of the settlements of this zone lies in their early application of the principles of estate planning being articulated by the ‘garden’ suburb or city planning movement and articulated in works such as Howard’s ‘Garden Cities of Tomorrow’ (1902) and Unwin’s ‘Cottage Plans and Common Sense’ (1902). The approaches laid out by this movement would prove highly influential on the suburban planning that dominated the expansion of British towns until at least the 1960s. These approaches were used by both private and municipal developers and supplanted the grid layouts of earlier terraced development and the traditional internal plans of housing. However, the widespread application of these low densities and ‘cottage style’ dwellings did not begin to be taken up on a large scale by either the speculative developers or the public sector until after the publication of the Tudor Walters report in 1919 (Crisp 1998, particularly ‘Introduction’ and ‘Chapter 5’).

Features commonly associated with this zone and influenced by the garden suburb movement include:

- Radial plans1 that frequently make use of concentric circles divided by axial roads (within Rotherham the clearest examples of this layout type are at Maltby and Dinnington).

- Generous provision of garden plots.

- Architectural forms referencing supposed ideas of vernacular character and tradition, particularly emulating idealised ‘cottages’; styles favoured to achieve this effect were generally influenced by the ‘Arts and Crafts’ revival of the late 19th century and the ‘Neo-Georgian’ school of architecture (English Heritage 2007b).

- Communal open spaces surrounded with cottages in the supposed tradition of English village greens 2 (although this is less common in Rotherham than in the comparable zone in Doncaster – greens were originally included at the centre of the Maltby roundel but have been compromised by later housing development).

Within this zone, the earliest applications of these ideas are best seen as examples of ‘model housing’ development. The concept of the model house has a long history within Britain, with one writer extending the concept back to Norman times - to the plantation settlements of the 12th and 13th centuries (Gaskell 1987, 4). The 18th century sees a more explicit use of the term ‘model’, used to denote a settlement planned as an example of best practice; this approach gained currency in a rural context on landed estates (ibid, 5; Muir 2000,138-140). In the later 19th century, model housing was seen to be a way to improve the living conditions of industrial workers, with such housing built by factory owners and other industrialists for their employees. The motivations behind this movement included the desire to create a more moral and ‘instructional’ environment for workers (Gaskell 1987, 14), as well as to enable conditions of improved hygiene and sanitation. Within the South Yorkshire coal field it seems probable that the creation of ‘model settlements’ was intended to provide housing that would be attractive to employees and their families, at a time when the mining of deeper seams required greater numbers of new labourers to be drawn from other parts of the country.

A related development to the creation of better housing in mining villages were the facilities originally provided by the Miners Welfare Fund, the product of a levy paid by colliery companies of 1d on every ton of coal produced following the Mining Industry Act of 1920 (Griffin 1971, 170). At colliery sites this fund provided pit-head baths, but within this zone notable features are welfare halls, recreation grounds and parks – often co-located in ‘welfare grounds’. This recreational provision has certain characteristics; team and spectator sports are well catered for, with football and cricket pitches at most grounds. Cricket grounds were often multi function, with tracks provided around their boundaries for cycling and athletics. Some grounds also included provision for tennis and bowling. Large areas of allotment gardens can also be seen on the 1930s OS plans within these settlements, although these are generally now in neglected conditions or have been overbuilt during the 20th century.

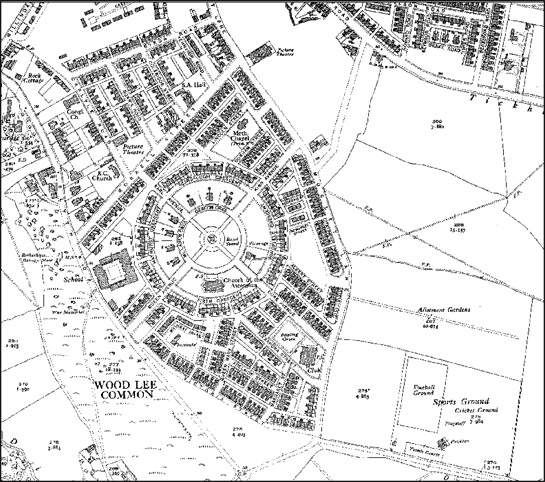

Figure 3: The plan of ‘Model Village, Maltby’, built in 1910, shows most of the characteristic features of this zone, including radial street plans, generous private and communal open spaces, miners welfare recreational facilities, churches for a variety of denominations, and an area marked by larger houses for middle and senior pit management.

1938 OS 6 inch to the mile mapping (not reproduced at scale) © and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 2008) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024

Clear organisational principles indicating the differentiation of status are apparent at most of these settlements. Most feature at least one detached house in its own grounds, designated for the overall pit manager, whilst some have further numbers of clearly larger houses in prominent positions. At Maltby ‘model village’ a ring of larger houses are situated at the hub of the main plan, overlooking a central green. The motivation behind such clearly visible and planned differentiation has been characterised by one writer as, “a visible reminder of who wielded power in an early twentieth century mining community” (Holland 1980, 67).

Institutional buildings contemporary with the planned villages reflect something of the dispersed origins of the immigrant communities attracted to them by work in their mines and by their high standards of living – village plans often include brick built Church of England, Roman Catholic and Methodist churches (Stratton 2000, 26).

Relationships to Adjacent Character Zones

The most obvious relationship between this zone and others is with the ‘Extractive’ and ‘Post Industrial’ zones, where the coal mining concerns that influenced their development are – or were - located. The wide variety of landscape types on which these collieries were sited (see ‘Extractive’ and ‘Post Industrial’ zone descriptions) means that the settlements of this zone are now sited amongst a range of enclosure types.

All of the character areas of this group generally abut or are closely located to historic villages described by this project under the ‘Nucleated Settlement’ zone description.

Inherited Character

The mines of this district often extended across large underground colliery ‘royalties’ [the areas of land from under which each company had rights of extraction] of up to 10,000 acres (Hill 1997, 16). These large royalty areas were a response to the increased cost of sinking the deeper pits necessary to penetrate the best coal seams (Hill 2001, 16). This economically determined pattern eventually resulted in the typical rural location of the settlements of the later coalfield, “each village being separated from each other by large tracts of countryside” (Jones 1999, 124), in stark contrast to the older colliery settlements, for example in the Dearne Valley, where settlements related to different collieries tended to merge into each other by the late 19th century. Here, collieries were much more closely spaced, each working areas of up to 3,500 acres.

Within this zone, character relating to earlier landscapes is generally rare. Exceptions include the boundaries of various phases of development, which generally coincide with historic enclosure boundaries, and earlier rural lanes that were incorporated into later planned designs.

Later Characteristics

On January 1st, 1947 a notice was posted at every colliery at the country reading,

“THIS COLLIERY IS NOW MANAGED BY THE NATIONAL COAL BOARD ON BEHALF OF THE PEOPLE” (NCB notice reproduced in Hill 2001, 36).

At the time of nationalisation, all assets of the former colliery companies, including 140,000 houses nationally, passed to the new coal board (Beynon, Hollywood and Hudson 1999, 2). The NCB continued to take a role in the construction of housing estates to attract workers up to 1976, when it withdrew from the provision of miners housing (ibid, 3).

The areas of social housing described here have, in most cases, undergone a widespread decline. Much debate has focused on the changes in government policy towards the nationalised coal industry and social housing during the 1980s and 1990s, a period in which all but one of the pits that supported this zone closed for good, with the vast majority of its working population directly involved in a violent and economically devastating industrial dispute (Adeney and Lloyd 1986). Following the dispute, large volumes of council and NCB owned social housing were transferred to the private sector. The sale of NCB housing in particular, undertaken in a very short period between 1985-8, has been blamed for physical and social decline within these settlements - much of the property being purchased by absentee landlords for very low prices (Beynon et al 1999, 3). More recently, regeneration efforts by the European Union and the ‘Housing Market Renewal’ programme have begun a process of regeneration in these areas.

Character Areas within this Zone

Map links will open in a new window.

- Brampton Planned Settlement (Map)

- Dinnington Planned Village (Map)

- Maltby Planned Settlement (Map)

- Sunnyside Planned Settlement (Map)

- Thurcroft Planned Settlement (Map)

- Wath upon Dearne Planned Settlement (Map)

Bibliography

- Adeney, M. and Lloyd, J.

- 1985 The Miners Strike 1984-5: Loss Without Limit. London: Routledge.

- Beynon, H., Hollywood, E., and Hudson, R.

- 1992 Regenerating Housing: Coalfields Research Programme, Discussion Paper 6. Cardiff: Cardiff University. Available From: http://www.cardiff.ac.uk/socsi/resources/regenerating%20housing%20-%206.pdf [accessed 04/08/2008].

- Crisp, A.

- 1998 The Working Class Owner Occupied House of the 1930s [Thesis: M.Litt in Modern History] Oxford University.

- English Heritage

- 2007a The Heritage of Historic Suburbs. London: English Heritage. Available from: http://www.helm.org.uk/upload/pdf/Heritage-Suburbs.pdf

- English Heritage

- 2007b The Modern House and Housing: Selection Guide – Domestic Buildings (4) [online]. London: English Heritage, Heritage Protection Dept. Available from: http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/upload/pdf/Domestic_4_Modern_House_and_Housing.pdf [accessed 04/08/2008].

- Gaskell, S.M.

- 1987 Model Housing: From the Great Exhibition to the Festival of Britain. London: Mansell Publishing Ltd.

- Griffin, A.R.

- 1971 Mining in the East Midlands 1550-1947. London: Frank Cass and Co.

- Hill, A.

- 2002 The South Yorkshire Coalfield: A History and Development. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd.

- Holland, D.

- 1980 Changing Landscapes in South Yorkshire. Doncaster: D. Holland

- Howard, E.

- 1902 Garden Cities of Tomorrow. London: S. Sonnenschein.

- Muir, R.

- 2000 The New Reading the Landscape: Fieldwork in Landscape History. Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

- Stratton, M.

- 2000 Twentieth Century Industrial Archaeology. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Taylor, W.

- 2001 South Yorkshire Pits. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Books.

- Unwin, R.

- 1902 Cottage Plans and Common Sense. London: Fabian Tract.

- Unwin, R.

- 1994 Town Planning in Practice: An Introduction to the Art of Designing Cities and Suburbs [originally published 1909]. Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press.

1 Radial ‘spiders web’ plans were championed in Ebenezer Howard’s original ‘Garden City’ proposals (1902, 50-57) as well as in Raymond Unwin’s development of the concept (Unwin 1994 [1909], 236)

2 Unwin believed that this arrangement would help engender community relations between the occupants of the cottages (Waithe 2006, 188)