Private Parkland

Summary of Dominant Character

The defining historic characteristic of this zone is the use of land as ornamental parkland, chiefly from the 17th to late 19th centuries, with many features created during this time continuing to have a major impact on current character. Character areas in this zone are frequently clearly defined from the surrounding countryside by circuits of walls or plantation woodlands that provide screening and enclosure; these may be broken or absent where agricultural use has been reintroduced within park boundaries. Trees and woodlands are an important feature of most of these landscapes, with deciduous plantation and ancient woodlands serving not only an ornamental purpose but also providing cover for game. Open areas are often punctuated by scattered trees, with the surrounding ground cover typically either permanent grassland maintained as pasture or, in many cases, managed for arable cultivation. The focal point of many of these parks is a large elite residence and related ‘home farm’ complex, sometimes on the fringe of an older village. In some cases no hall survives.

Common design features in these character areas are generally intended to emphasise the high status of their original owners. Such features can include ornate gateways and lodges; tree lined avenues and curving driveways; architectural follies, statuary, fountains and summerhouses; artificial lakes and ponds; formal gardens; and kitchen gardens.

Relationship to Adjacent Character Zones

The distribution of the character areas within this zone relates, in the east of the district, to areas of farmland economically productive during the 18th and 19th centuries, and now largely within the ‘Agglomerated Enclosure’ zone. In the west, the ‘Thundercliffe Grange’ and ‘Wentworth Park’ character areas are closely related to the ‘Assarted Enclosure’ zone.

The group of parklands along the eastern boundary of the district can be associated with the known concentration of parkland that continues across the border into the Doncaster district and is found in relation to the historically productive agricultural landscapes of the Southern Magnesian Limestone (Countryside Commission 1996).

Inherited Character

The setting aside of large tracts of land for the exclusive use of a small restricted and powerful social group can be traced back to at least the 12th century in South Yorkshire. The medieval landscape of South Yorkshire included at least 26 specially enclosed or imparked areas, created specifically to enclose a population of deer for hunting (Jones 2000, 91). Some medieval deer parks evolved in the post-medieval period into purely ornamental landscape parks. In Rotherham, ‘Thrybergh Park’ is an example of this process - representing a part of a larger medieval deer park – and part of the ‘Thundercliffe Grange’ character area overlaps with the area of the medieval Kimberworth deer park. Medieval deer parks performed a much less aesthetic function than their post-medieval counterparts, but nevertheless required considerable maintenance, representing a significant investment in land resources. Most were being broken up by the 16th and 17th centuries as these maintenance costs stretched their owner’s resources (Rackham 1986, 126).

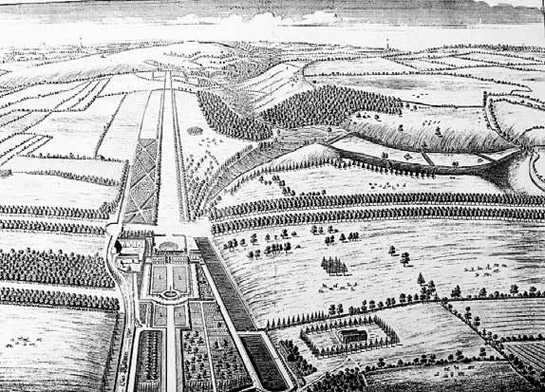

Following the European renaissance, the idea of parkland was reborn as a focus for display of status and wealth through the aesthetic manipulation and presentation of land. Early examples, established before the mid 18th century, took their influences from formal continental models, particularly the gardens of the Palace of Versailles. Internal patterning was based on the geometric division of space, through the use of features such as low parterre hedges, regular straight avenues of trees, and rectangular ‘canals’. Ravenfield, Wentworth Woodhouse, Sandbeck and Kiveton Parks are all known to have been originally landscaped in this style.

Figure 1: Ravenfield Park in the 1720s, as drawn by Thomas Badeslade for Campbell's ‘Vitruvius Brittanicus’. This image shows a clear example of the formal, geometric style that dominated 16th and early 17th century parkland designs.

During the 18th century this formal aesthetic was challenged by English landscape designers such as Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown [1716-1783] and Humphry Repton [1752-1818] (Rackham 1986, 129). The influence of the introduction of this new style on landscapes in Rotherham is clear, with Brown and Repton known to have worked on the remodelling of Sandbeck and Wentworth Woodhouse respectively in the late 18th century (English Heritage 2001). The naturalistic approach, exemplified by the designs of these parks, was concerned with the reproduction of idealised rural landscapes, such as those depicted by 16th century painters like Lorraine, Poussin and Rosa, in reaction to the formal style that it replaced (Darby 1951 389). By sponsoring the naturalistic transformation of formal parklands it can be argued that the owners of these estates were not only following fashion but providing themselves with an opportunity to show their appreciation of aesthetics to their peers.

Figure 2: Ravenfield Park, as depicted on the 1851 6 inch OS map. Since Badeslade’s depiction, the park has been relandscaped, with thinning of the formal plantations and avenues into more naturalistic clumps.

© and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 2008) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024.

There little evidence in Rotherham for the deliberate clearance of earlier villages at the time of imparkment. This is in contrast with Doncaster, where evidence exists for dramatic reorganisation of at least half a dozen villages (see Doncaster’s ‘Private Parkland’ character zone). However, buildings constructed in clear ‘estate’ styles can be found at Firbeck and Wentworth, whilst the main streets of both Wentworth and Ravenfield villages take sharp diversions as they reach the park boundary, hinting at deliberate diversion. The reworking of existing rural forms is a common feature within estate countryside and has been associated by some authors (see Roberts 1995, 2-4; Newman 2001, 105) with the creation of an idealised countryside by landowners, physically and historically separated from the truth of its past.

The 18th and 19th century creation of many of these parks also served to preserve a number of pre-existing boundary and earthwork features from earlier agricultural landscapes. The designers of parklands would generally set out to create, “an appearance of respectable antiquity from the start, incorporating whatever trees were already there” (Rackham 1986, 129). This approach is most likely to have fossilised earlier steeply sloping ancient woodlands and boundary features along the edges of parks.

Later Characteristics

Figure 3: Sandbeck Park. The legibility of Sandbeck Park has been reduced by the reintroduction of arable cultivation within the park boundary in the 20th century.

Cities Revealed aerial photography © the GeoInformation Group, 1999.

The pressures on owners to maintain these large tracts of land and their accompanying mansions appears in most of the cases in this zone to have been too great to maintain their use as originally designed. All character areas within this zone include substantial areas of arable cultivation, introduced within the park boundary during the 20th century. This process reduces the legibility of the earlier parkland, by reducing the contrast between it and the surrounding enclosed land.

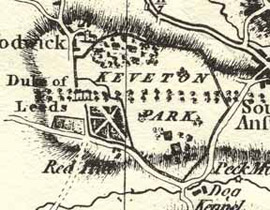

At some sites within this zone the conversion of parkland (back) to arable production was underway by the early 19th century. The mansion at Kiveton Park, formerly set in an extensive geometric parkland (depicted in Vitruvius Britannicus (Campbell 2006 [1725]) and the seat of the Duke of Leeds), was disimparked in 1811 (Hunter 1828, 144). The resulting changes in the landscape can be clearly seen through comparison of Jeffreys’ 1775 map and the OS 1st edition of 1851. The only legible traces of the park today are parts of the original stone boundary wall and some outbuildings around the replacement Kiveton Hall, built in the 19th century as the farmhouse to the new farmland.

Figure 4:: Above left- Kiveton Park as depicted by Jefferys in 1775 and - above right – the Kiveton Park character area as shown on the 1851 6 inch OS map. Since 1851 most of the internal boundaries within the park boundary have been removed.

© and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 2008) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024.

There is a local tradition that the demolition of the mansion at Kiveton by the 6th Duke was as the result of a lost bet with the future George IV, although this story was denied by later managers of the estate (Darley 1929, 188-189). The documentary evidence seems to point to a purely economic motive behind the disparkment. In 1845, the 7th Duke brought a successful case in the Chancery Courts, following the death of the 6th Duke, against the other beneficiaries of his father’s will for compensation for ‘Equitable Waste’ – arguing that his father had not been legally entitled to profit from the conversion of the park to farmland (Smith 1850, 155-125). The inheritance of the 7th Duke was restricted only to the estates ‘held in tenant’ by his father; the son argued that the estate inherited by other beneficiaries included the proceeds of the ‘equitable waste’ represented by the disparkment of Kiveton, which should by right have been his.

At Wentworth Woodhouse radical changes to the appearance of the parkland have taken place in the 20th century. The early landscape history of this central part of the Wentworth Woodhouse estate is thinly recorded in historical sources. The estate was acquired by William de Wyntword by his marriage to Emma Wodehous in the 13th century (English Heritage 2001). The element 'Woodhouse' appears in many two part placenames and is thought to indicate "the house in the wood" (Smith 1961, 121). It is difficult to trace earlier landscapes in the heavily ornamented landscape that now makes up the park area, but it is possible that the area was heavily wooded until its clearance by the Wentworth family. A medieval hall is thought to have been replaced in 1630 by the first Earl of Strafford; the present house, which features the longest country house façade in Europe, is in fact two 18th century houses built back to back and extended in subsequent decades. The grounds, which feature 18th century monuments, ornamental woodlands, a mausoleum, lakes, cascades and pyramids, was already landscaped by the mid 18th century when it was reworked by Humphrey Repton c1790 (ibid).

Figure 5: The East Front at Wentworth Woodhouse.

© Johnson Cameraface, used according to a creative commons licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/deed.en_GB)

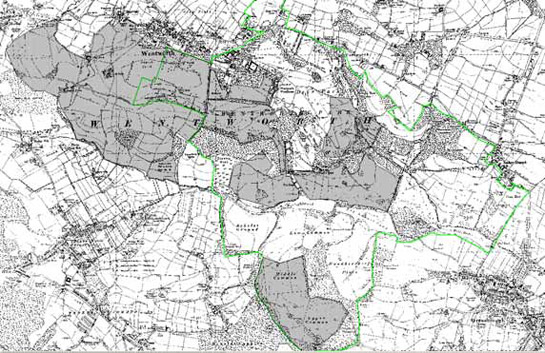

The great wealth of the Fitzwilliam family in the post-medieval period was largely built on their ownership of large amounts of land across the coal measures between Rotherham and Barnsley. By the time of the 6th Earl’s death in 1902 the wealth of the family was measured at £2.8 million, equivalent to more than £3 billion in 2007 (Bailey 2007, xvii), before taking into consideration the family’s substantial annual income from coal royalties - all in all more than sufficient to support the extravagance of the largest private house in Britain, set in expensive, high maintenance parkland. Paradoxically it was the great mineral wealth physically and metaphorically underpinning the family seat that would lead to the decline of the designed landscape left by Repton. The Second World War necessitated the adoption in the UK of open cast coal mining and by 1943 the extraction of coal from beneath the Wentworth estate (but still outside the boundaries of the park) was already underway (Hansard 1943 Vol. CXXIX, Col. 617). Following the war, the newly elected Labour government wished to continue mining these reserves, extending the area of the land requisitioned to within the park boundaries. Despite opposition from the 8th Earl, local people, the Campaign for the Preservation of Rural England, the National Trust, a committee of mining engineers and geologists from the University of Sheffield, and even from the Yorkshire president of the NUM, the government insisted on proceeding with the extraction of coal from within the park itself (Bailey 2007,398). This had a dramatic effect on Repton’s landscape. A representative of the National Trust recorded that,

“One of the [areas worked] is the walled garden. Right up to the very wall of the Vanburgh [west] front every tree and shrub has been uprooted … Where the surface has been worked is waste chaos and as [my colleague] said, far worse than anything he saw of the French battlefields after D-Day” (quoted in Bailey 2007,398).

Comparison of OS mapping of the estate pre- and post-extraction demonstrates that the landscape was generally not restored in a manner that exactly reproduced its earlier features. The register of Historic Parks and Gardens for Wentworth Woodhouse notes that,

“The character of the landscape was altered as the levels were not restored in every case and replanting was not informed by an appreciation of vistas and views. The subtleties of the views, particularly those towards Temple Hill and from the south terrace, have been lost” (English Heritage 2001).

Figure 6: Comparison of the layout of countryside before and after opencast operations south of Wentworth Village.

© and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 2008) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024.

Figure 7: War time and post-war open cast mining (grey shading) in relation to Wentworth Park (green boundary) and its surrounding estate countryside - open cast areas interpreted from analysis of changes apparent on OS mapping between 1938 and 1955, descriptions in English Heritage 2001 and information abstracted from Bailey 2007.

© and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 2008) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024.

Character Areas within this Zone

Map links will open in a new window.

- Aston Park (Map)

- Firbeck and Langold Parks (Map)

- Kiveton Park (Map)

- Ravenfield Park (Map)

- Sandbeck Park (Map)

- Thundercliffe Grange (Map)

- Thrybergh Park (Map)

- Wentworth Park (Map)

Bibliography

- Bailey, C.

- 2007 Black Diamonds: The Rise and Fall of an English Dynasty. London: Penguin.

- Campbell, C.

- 2006 [1725] Vitruvius Britannicus or the British Architect. Mineola NY USA, Dover Publications Inc.

- Countryside Commission

- 1996 Southern Magnesian Limestone: Character Area 30 [online]. London: Countryside Commission. Available from: www.countryside.gov.uk/LAR/Landscape/CC/yorkshire_and_the_humber/southern_magnesian_limestone.asp [accessed 4 February, 2008].

- Darby, H.C.

- 1951 The Changing English Landscape. The Geographical Journal, 117, 377-394.

- Darley, Rev. Can.

- 1929 Notes and Queries- Kiveton Hall. Transactions of the Hunter Archaeological Society, Vol 13, 188-189.

- English Heritage

- 2001 Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England: South Yorkshire [unpublished]. London: English Heritage.

- Hansard

- 1943 HL Deb Coal: Open Cast Mining, 9th Nov 1943 Vol. CXXIX, Col. 617.

- Hunter, J.

- 1828 South Yorkshire: the history and topography of the Deanery of Doncaster in the diocese and county of York. London: Joseph Hunter / J.B. Nichols and Son.

- Jones, M.

- 2000 The Making of the South Yorkshire Landscape. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Books.

- Magilton, J.R.

- 1977 The Doncaster District: An archaeological survey. Doncaster: Doncaster MBC Museum and Arts Service.

- Newman, R., Cranstone, D. and Howard-Davis, C.

- 2001 The Historical Archaeology of Britain c.1540-1900. Stroud: Sutton Publishing Ltd.

- Rackham, O.

- 1986 The History of the Countryside. London: J.M. Dent.

- Roberts, J.G.

- 1995 Altered by the hand of taste: halls, parks and landscapes in the Doncaster area of South Yorkshire, 1660-1850. BA(hons) dissertation, Department of Archaeology and Prehistory, University of Sheffield.

- Smith, E.F.

- 1850 Reports of cases argued and determined in the English Court of Chancery, with notes and references to both English and American decisions Vol. XXII. New York: Banks. Gould and Co.