Early to Mid 20th Century Municipal Suburbs

Summary of Dominant Character

The stereotypical pattern of development within this zone is one of large scale land acquisition by Sheffield City Council, rapidly followed by the laying out of housing around formal geometrical street plans based on intersecting circles with open greens, institutional buildings and retail areas placed at the hubs of these radial streets.

Figure 1: Manor and Woodthorpe Estates, as depicted by the Ordnance Survey in 1938. The radial plans of these estates were influenced both by the Garden City movement and also by the model settlements developed by colliery companies in the region in the early 20th century.

Historic mapping © and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 2008) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024

These estates generally employed a variety of stock patterns for the blocks of “minimal Neo-Georgian” cottages (Harman and Minnis 2004, 29), which were normally grouped in short terraces of two, three or four dwellings and built of red machine-formed textured brick. Cul-de-sacs are rare, with most roads forming circuits, and houses were generally aligned to a repetitive pattern, with small front and larger rear gardens. It is rare for houses to feature no private outside space. As a consequence, most of the residential units in these zones are recorded by the characterisation project as being of medium density, with an average 25-55 dwellings per hectare.

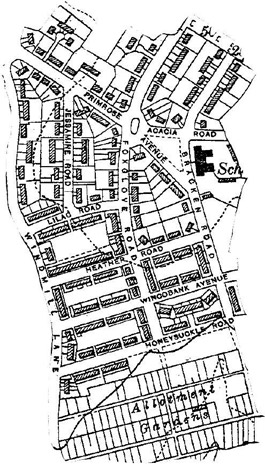

Sheffield’s earliest municipal cottage estate was built at Wincobank, in the east of the city. This estate was constructed following competitions organised by the Corporation for design aspiring in its principles “as far as possible, to ... a miniature garden city” (City of Sheffield, 1905, 11). The estate’s plan represents the transition of Sheffield Corporation developments from the grid iron patterns and tenement blocks they began the 20th century with, to the more spacious cottage estates that would become so characteristic of the 1930s. Early cottages on the estate were built to a grid iron pattern, around regular open spaces to the designs of architect Percy Bond Houfton (responsible in 1896-8 for Creswell Model Village for the Bolsover Colliery Company). Houfton’s houses were some of the first in Sheffield built for workers to provide not only internal toilets but also (in the ‘Class B’ houses) upstairs bathrooms. These houses were built with both an individual private back yard and a small front garden. A later phase of the estate (the design of which was presented at the Yorkshire and North Midland Cottage Exhibition of 1907) dispensed with the formal grid in exchange for a more ‘Picturesque’ layout, which mixed the “formality of a central axis (Primrose Avenue), with… the informality of gently curving estate roads” (Harman and Minnis, 2004, 186). A number of different building designs were constructed within this estate, some of which appear to have formed the basis of cottages designs that were rolled out across other Sheffield estates built in the 1930s.

Figure 2: The Flower Estate illustrates the evolution of Sheffield’s Cottage Estates in the early 20th century. Houfton’s cottages (making use of central greens) are found in the south, whilst the slightly later ‘exhibition’ houses, arranged on gently curving principles, are in the north.

1922 OS map extract © and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 2008) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024

Primary schools are provided across this zone at regular intervals, the typical design mirroring the Neo-Georgian facades of the housing but otherwise employing ‘open-air’ principles, with sliding partitions opening from classrooms onto open courtyards (ibid).

Landscaping of the streets is generally harsh, with few street trees included in the designs (notable exceptions to this being at Longley and Wisewood, where some mature trees are a feature). Ornamental and recreational space in this zone was less often of the parkland character common in Victorian or early 20th century suburbs, with open spaces generally reserved as recreation grounds (often featuring pavilions and spaces for team sport), or as allotment gardens.

Inherited Character

As a rule the Sheffield cottage estates did little to preserve existing landscape features. These developments still represent one of the largest single and wholesale alterations of landscapes since the enclosure acts of the late 18th and early 19th centuries improved large swathes of moorland.

Later Characteristics

By the early 1950s it was apparent to Sheffield’s Housing Development Committee that the designs executed within this zone would not be able to address the acute housing needs of the post-war period, not least because the land available for development was too limited to meet the demands of these medium density housing schemes (Harman and Minnis 2004, 32-33). This led the city architect’s team to actively seek out modernist systems of building and planning, which could take account, on one hand, of sites previously undeveloped because of their steep terrain or unfavourable north facing aspect, and, on the other hand, of systems that could facilitate rapid development on central ‘slum clearance’ sites (Sheffield Corporation 1962, 6).

A number of the character areas in this zone were finished during this period of architectural change in the city. This process is most noticeable at the shopping areas added to these estates in the 1950s and 1960s, although Manor Park also has considerable numbers of modernist maisonette units.

Later in the 20th century council tenants in these areas were encouraged to buy their homes and there were fewer government incentives for councils to build housing (Short 1982, 59). A number of council houses moved into private hands in this time. This is part of a nationwide trend where home ownership has increased and council renting decreased since the 1970s (Office for National Statistics 2004, 30).

This trend has led to more housing being built by private developers, a trend that has itself led to the development of large late 20th century suburbs. Within the ‘Municipal Suburbs’ zones there has been infilling with privately built housing, as well as an expansion of private housing surrounding them.

A number of these estates have seen major redevelopment in recent years, with large areas demolished (particularly in the Manor and Parson Cross areas) and replaced with new housing. This programme has resulted in large scale ‘interstitial’ landscapes of dereliction and scrub, current during the time of this project, but mostly scheduled for redevelopment under the Housing Market Renewal programme.

Character Areas within this Zone

Map links will open in a new window.

- Arbourthorne (Map)

- Ecclesfield Estates (Map)

- Manor Park Estate (Map)

- Manor and Woodthorpe (Map)

- Parson Cross / Shiregreen (Map)

- Wincobank and Grimesthorpe (Map)

- Wisewood Estate (Map)

- Wybourn (Map)

Bibliography

- Doe, V.

- 1976 Some Developments in Middle Class Housing in Sheffield. In: S. Pollard and C. Holmes (eds.), Essays in the Economic and Social History of South Yorkshire. Barnsley: South Yorkshire County Council, Recreation Culture and Health Dept, 174-186.

- English Heritage

- 2000 Norfolk Park, Sheffield – Entry on Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest, London: English Heritage.

- Cary, J. (engraver)

- 1795 A Map of the Parish of Sheffield in the County of York. 3¼ inches: 1 mile. Sheffield: Wm Fairbank and Son.

- City of Sheffield

- 1905 Handbook of Workmen’s Dwellings. Sheffield: City of Sheffield.

- Geological Survey of Great Britain

- 1974 Sheet 100 Sheffield – Solid and Drift, 1:50,000. Southampton: Ordnance Survey for the Institute of Geological Sciences.

- Harman, R. and Minnis, J.

- 2004 Sheffield: Pevsner Architectural Guide. New Haven and London: Yale University Press

- Hunter, J.

- 1869 Hallamshire: The History and Topography of the Parish of Sheffield…” Sheffield: Pawson and Brailsford.

- Scurfield, G.

- 1986 Seventeenth Century Sheffield and its Environs. The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 58 (1986), 147-171.

- Sheffield Corporation

- 1962 Ten Years of Housing in Sheffield 1953-1963 Sheffield: The Housing Development Committee of the Corporation of Sheffield